Welcome back to Scare Me! a weekly horror newsletter. Today, we’re speaking with Nat Cassidy, the author of horror novels including Mary: An Awakening of Terror and Nestlings.

I was having a particularly hard day when I abruptly left my apartment, got in my car, and drove to Barnes & Noble. It was a hot summer day in 2023, and my mental health had been fragile for a while.

I beelined to the horror section, and there it was: Nat Cassidy’s Mary. Back at home, I set the book down on my nightstand and stared at it. It was a long book, I reasoned, and by the time I finished reading it, I would probably feel better.

I was right. Mary whisked me away to the Arizona desert, where ants marched in determined columns and cult members organized rituals and ghosts haunted bathtubs. It was batshit crazy horror, and an absolute delight. By the time I finished reading Mary, I knew I’d buy anything Nat Cassidy wrote next.

Stephen King agrees with my assessment. “Get your claws into this one, horror fiends. It's terrific,” he wrote of When the Wolf Comes Home, Nat’s most recent novel. “Sink your teeth into a classic.”

It’s been a busy year for Nat. On the day we spoke, he was in the midst of edits for a short story that will be included in I Know a Place, the 2026 reissue of his novella, Rest Stop. A few weeks earlier, he submitted the first draft of his next novel for Tor Nightfire.

And he’s barely finished promoting two bestselling 2025 releases: his astonishing and action-packed When the Wolf Comes Home and a contribution to The End of the World as We Know It: New Tales of Stephen King’s The Stand.

But before Nat’s horror novels were flying off shelves worldwide, he had a long career as a celebrated actor and playwright. I was curious about how these two halves of his creative life fit together, feeding one another and adding up to Nat’s unique ability to craft scares that pack a serious emotional gut-punch.

This is a long interview—I genuinely could not bring myself to cut one more word—so your email might be truncated. If that’s the case, click the “Read Online” option in the top right corner. It’ll take you to the web version!

Thanks for reading Scare Me! Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to receive a new edition every Thursday.

Michelle Delgado: You've had so much work come out this year. Do you get to take a break, or is it just full steam ahead? It sounds like you're still in the thick of it.

Nat Cassidy: I think that's pretty accurate. I had a novella come out with a brilliant indie press, Shortwave, in 2024. Shortwave is absolutely brilliant—they finally got this great distribution deal with Simon & Schuster, and because Rest Stop did well enough, we want to reissue it so it can get into bookstores. But we were aware that plenty of people had already bought it. So we were like, “How do we repackage it and sweeten it so that people want to buy it again?”

We [decided to] include all these other short stories I've already written. And then I was like, “Why don't we include five new short stories too?” Which was a perhaps overly ambitious idea of mine, which I'm wont to have every now and then. Once we started doing the math of when everything was going to need to be done, it was like, “Oh, shit. Write all these short stories right now.”

I'm working on the very last one, which I saved for last because I was like, “This will be the easiest one to write!” Of course, it has now proven to be the most difficult. I don't even know if it's going to wind up in the collection.

You’re working on a novel as well. Kids on bikes, I believe?

I just turned in the first draft of my next Nightfire novel right before Thanksgiving, and as you said correctly, it's kind of my homage to kids on bikes. It's about…what is it about? I've yet to have to speak about it, so you're going to hear me waffle through it in real time.

It's about [XXXXX] and [XXXXX] and [XXXXX]. There is, in the world of this book, a [XXXXX] that can [XXXXX]. They even sell [XXXXX]. And the way to generate these [XXXXX] is [XXXXX]. You can either do that with your own [XXXXX] or you can [XXXXX].

This group of ten-year-old kids is [XXXXX], because they're very precocious, and they discover a [XXXXX] that [XXXXX]. They kind of get roped into [XXXXX] and the horrible web of [XXXXX].

It's incredibly depressing. The first draft is very rough, so there's a lot of work to be done, but I'm very excited about it. I think it's really going to ruin people's day.

Editor’s note: I’m still not sure how, but Tor Nightfire somehow caught wind of our conversation. At this point in the interview, they sent a deluge of drones that descended from the sky and knocked angrily against my windows. After tense negotiations, I got them to back down by agreeing to redact the plot details. I’ll share more when this information is declassified next year.

It's hard to think of something sadder than what you did in When the Wolf Comes Home, but it sounds like this might top it. I can't wait to read it.

I hope you enjoy it up until the ending. And then I hope the ending ruins…let’s say, a week. I hope it casts a pall over, like, a week.

I was listening to a podcast recently and heard you mention that you’re a trained Shakespearean actor. It got me rethinking Shakespeare’s tragedies—I realized for the first time that you could credibly argue that they’re horror stories. I mean, King Lear scarred me for life.

Right? Literally, pull a dude's eyeballs out and stomp on them in King Lear. Out, vile jelly!

I'll try not to go into egregious detail, because I've told part of this story before, but I was always a macabre kid. I’ve loved horror for as long as I have been conscious—anything spooky, or full of ghosts and goblins and murder, was a great way to get me to pay attention.

When I was in first grade, I was an absolute piece of shit kid. I was such a nightmare. Disruptive, literally setting fires in the back of the room, carving swear words into the walls and the desk. My first grade teacher hated me, and I hated her.

She was Greek—from-Greece Greek. One day, she was showing the class slides from a trip to Greece that she had recently taken, and one of the slides was this old amphitheater. For some reason, she started telling us about how she saw a production of Macbeth there. She starts telling this group of six-year-olds the plot of Macbeth, which is a dubious prospect. But to her credit, she noticed that I stopped doing whatever I was doing to pay attention as soon as she started talking about witches and regicide and curses.

Whenever next she had to pull me by my earlobe to the front of the room, she basically dared me, since I thought I was such hot shit, to read Macbeth. As a first grader. And because I wasn’t going to back down from a challenge, I was like, “Okay, I'll read it. I'll show you.” It was this little extra credit assignment. Me and my mom sat down and read Macbeth every night, little chunks at a time. Ninety percent of it probably flew over my head, but I got enough of it that I was like, “Oh my God, this is absolutely a horror story.”

I became obsessed with Shakespeare from that point on. I pretty quickly moved on to Hamlet and Othello and The Tempest, which wasn't scary, but at least there were fairies and witches and little monsters. And Midsummer Night's Dream, which I loved. I thought it was hilarious, but it also wasn't scary.

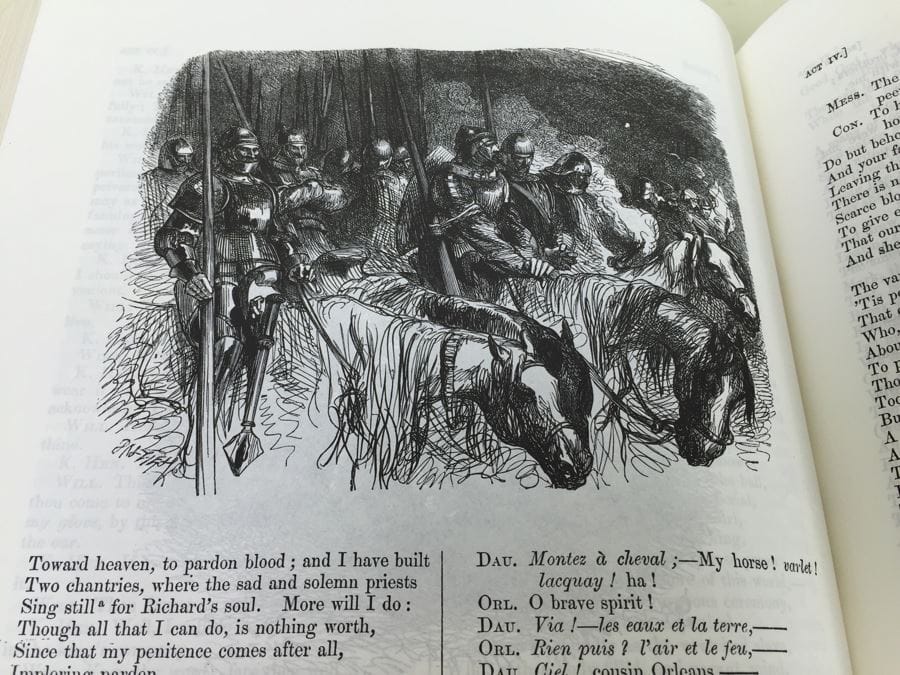

I was reading a collected works that we got from Costco for $3 or something like that. I'm forgetting the name of the artist—I don't think it was Gustave Doré, but it had line cut Doré-esque illustrations for each of the plays.

But you can already see: When I commit to a thing, I commit to a thing. I became this little obsessive Shakespeare nerd. I was already a precocious child actor at that point, so I pretty quickly dedicated the acting side of my life to pursuing Shakespeare and to the classics. I knew I wanted to write horror stories from a very early age, and I knew that as an actor, I just wanted to do Shakespeare.

I was born in ‘81, so by the time I was really coming online as a conscious being, Kenneth Branagh fever was sweeping the nation as well. I got caught up in his Henry the Fifth and Much Ado, and the Oliver Parker Othello that he was Iago in, and then Hamlet. I would just watch them obsessively, I wanted to be a little Kenneth Branagh.

Shakespeare was a populist entertainer. We don't do him any favors in our education system by treating him like this revered, iconic totem of poetry and language. He is all that, but he was also a dude writing potboilers for an audience of ninety-nine percent illiterate people who would throw rotten fruit on the stage if they got bored for even a second. Even though there is some of the greatest poetry our language has ever produced, these stories are full of fart jokes and dick jokes, witty repartee and murder and betrayal and really base, vulgar plot mechanics.

Since time immemorial, one of the most reliable genres for our weird little species is horror. Monster stories, murder, revenge, and all these looked-down-upon tropes have been with us for as long as we have been able to tell stories. I feel a little like the cool English teacher saying this, but there's really no difference between Titus Andronicus and a Quentin Tarantino movie. It is just floor to ceiling gore and murder and these punk-ass characters trading insults with each other. It's very grindhouse.

The most vaunted play in the English language is Hamlet, and that's just a ghost story that turns into a revenge drama. There's a direct line between Hamlet and Oldboy. King Lear is one of my absolute favorite Shakespeare plays, and it’s about a family falling apart, and that family happens to be the royal family, and it leads to all these apocalyptic consequences. People are killing and betraying each other left and right.

Stephen King was the other author that I was absolutely obsessed with at that age, and continue to be, and they were scratching the same itch.

I was raised by a single mom who had to work and also had MS—so when she wasn't working, she was usually resting. Because of that, she couldn't be super controlling over what me and my brother were reading or doing. She was also a huge horror fan. I came to Stephen King through her. She was like, “You can read whatever you want, but if you get scared, learn how to take care of yourself. Don't read anything you feel is too much for you.”

It was a single parent, part-time employed household, so we didn't have any money. But we were living right next to a library. She was like, “You can get whatever you want out of the library, but for every horror novel you take out, you have to take out one classic.” That was her diet that she put me on. And she never stipulated what a classic meant, so it could be anything up to my discretion. I could take out a book by Clive Barker, and as long as I took out Dracula or Frankenstein, that was okay.

Besides Shakespeare, I quickly moved on to Dostoevsky. I kind of became obsessed with Dostoevsky for a little while. Again, thirty to forty percent of it went over my head the first time I read it. But there's a great ax murder scene in Crime and Punishment. I just fell in love with the more respectable side of horror, and the more horrific side of respectable literature.

From a very early age, the literary and the horrific were never mutually exclusive. It was always a very porous border between the two of them. And that's probably one of the major reasons why I'm also very bullish and defensive of my genre to this day. I had to be in the ‘90s, because horror was that kind of a nadir at that point, critically speaking. People really looked down on it, and I would get a lot of shit for always having a Stephen King book on me. But all it took was saying, “You know, this is no different than King Lear or Hamlet,” and they would have to walk back some of their snide dismissal of it. So I'm grateful that I had those tools from an early age to disprove the naysayers.

That was such a long, rambling answer.

No, that was magnificent! That was everything I was curious about.

I've never really gone this deep into nerdery before, but if people do like Shakespeare and don't know some of his other contemporaries or immediate successors, check out the Jacobean revenge drama fad.

The Jacobean era is basically from the 1600s on—authors like John Webster and Cyril Tourneur and Thomas Middleton. Plays like The Revenger's Tragedy and The White Devil [came out] towards the end of Shakespeare's career and a few decades extending past it. They are some of the bloodiest, nastiest revenge horror stories you can ever imagine on stage.

They don't quite have the poetry of Shakespeare, because he was such a singular author. But if you like that time period and aesthetic—dramas in blank verse and whatnot—I highly recommend them.

I feel like people are forgetting about John Webster and that school of playwriting, because he doesn't get done that much. But oh my god, they're so bloody and violent. People are poisoning everything—there's poison skulls and poison books—and people stabbing everybody left and right. It's delightful. The tie between horror literature and Elizabethan and Jacobean drama is very strong.

I'm definitely not well versed in my Jacobean revenge dramas, so this is a good rabbit hole!

Something I've been thinking about lately is the tension between horror stories that are warm-hearted, hopeful, and maybe even wholesome—and stories on the opposite pole, which are relentlessly bleak and depressing.

As someone who writes on the tragic or the bleak side of things, is that kind of a polarity that you're exploring in your work?

That's a great question. I love that question. I think of something Neil [McRobert] talks about—I'm going to paraphrase him six ways to Sunday, to the point where he might not have ever said these exact words, but I think the spirit of the sentiment holds true, and it's something that I one hundred percent agree with.

It’s that in every horror story that I like, the actual engine of the story is not that bad things happen, but that there are people who stand up to the bad thing. The story is not “this bad thing is happening”—the story is “this bad thing is happening, and here's a character who's going to try and survive it.”

I find that to be the holy purpose of the genre. In general, storytelling is such a vital tool to our species, because we use it as a learning mechanism. That's one of the reasons we are always so hungry for stories—stories are essentially little instruction manuals that we give ourselves. How would this person react in these given circumstances? What would I do if I were this person? What are the options I have at my disposal? What examples do I want to follow, or explicitly not follow?

When we sit down to watch a horror story, they're these little instructive seminars of like: What do you do when you're grieving? Well, you don't bury your relatives in the pet cemetery. I know you really want to, but here's why that's a bad idea.

Maybe you won't have that literal option at your disposal when you lose someone you love, but you will understand what it means to desperately want to get that person back. You’ll need a story that tells you that sometimes you gotta make peace with loss. That's the whole transitive experience of genre fiction.

I think, by and large, most people are capable of immense goodness, and so horror stories kind of lose their instructional value if they are unremittingly bleak. Sometimes there's a perverse thrill—and I don't mean that in a judgmental way, perverse thrills can be super fun—but sometimes there's the perverse thrill of watching a movie just being bleak.

But the stories that I find the most engaging and the most emotionally affecting are the ones where I'm like, “these are these are decent, flawed people going through something, and I see myself in them, and I want to avoid that fate ever befalling me.” I get that much more invested in the story.

Usually, in the stories that I love the most, there is a hopeful ending, but that hope is changed—is transmogrified—by the events of the story into this new thing, this almost undefinable thing that you then carry with you after the story is completed. You investigate it, you swish it around in your mouth for sometimes years to come.

You mentioned the word tragedy, and I think that is exactly it. Most great horror stories, I think, carry the baggage of classical tragedy with them. If you really want to get into the weeds of Aristotelian theory and things like that, you've got hamartia and the tragic flaw, and all the dramatic irony. These things really just come down to the sort of perversion of promise and the the betrayal of heroic capability. This actually gets mentioned in the book I am working on.

I think a lot about how what makes a tragedy. A tragedy is when a compelling character is in the wrong story. If Othello is in Hamlet, there's no story—because the ghost will tell Othello, “I've been murdered, revenge me,” and Othello will go, “Oh, okay.” And then that's the end of the play. If Hamlet is in Othello, there's no story, because Iago will fuck with him, and Hamlet will be like, “I don't know if I believe you.”

A tragedy is when there's a compelling character, but they have that flaw that makes them blind to the obvious in that story. And then we watch them, and sometimes we want to shout at them, “Oh my god, what the fuck are you doing? Why are you doing it that way? Get out of there!” But because of their personality, and because of the circumstances and fate that they find themselves in, they go through to this tragic end.

How many times do we do that in our own fucking lives? How many times do we not investigate our own shortcomings and blind spots and biases that ultimately lead us down very destructive paths? The gift of tragedy as a storytelling device is that if we're willing to pay ourselves that same sort of analysis, sometimes we can avoid really bad things down the line.

All of this relates to that idea of art in horror, then, because that is the way we keep these stories from being didactic screeds. We have to constantly remind ourselves that the characters are just like you and me. They're full of hope and dreams and promise and love, because they are just like you, reader! And so pay attention! Pay attention to these bad things that are happening. Pay attention to these good things that are happening, and don't for a second delude yourself into thinking that you can avoid this fate without a whole lot of effort and a whole lot of awareness.

Really, all horror stories, in the end, are dealing with the fact of death. That is our life's journey, and [we] spend whatever time we have rectifying the fact that this is the only time we've got, as far as we know—that there is an endpoint down the line. The less willful ignorance we have going into our understanding of our mortal existence, the better.

You're clarifying something for me. I'm thinking about some of the most memorable books I've read this year—Exquisite Corpse by Poppy Z. Brite, The Lamb by Lucy Rose, and Earthlings by Sayaka Murata—and all of those end in tragedy, depending on your interpretation.

But to your point, the characters make choices at every step that feel completely logical. They're just in such weird circumstances. It's strange to say, “I read a book about cannibal serial killers, and it had a lot of heart.” But Exquisite Corpse did!

The ending of Earthlings, arguably, is a triumph! I don't want to spoil it, but they're transcending taboos. It’s a delightful little permission structure that horror is allowed to indulge in, and I think that is an important and beautiful thing. You know, stories are empathy machines—and the more we can empathize with even the most outrageous of taboo breakers, the stronger we get as a species.

I did see a lot of people who maybe read more literary fiction accidentally fall into Earthlings, and I feel like there's a huge misunderstanding of that book. The horror is society! The horror is someone trying to make this woman have a baby that she doesn't want to have! The final taboo is funny, in a way.

[It’s a] middle finger to the constraints that are being forced upon her. Isn't that the most satisfying thing to witness?

It's always funny when there are horror crossovers with the literary community. I think a lot about when Cormac McCarthy’s The Road came out, the lit crowd was like, “Oh my god, this is the bleakest, most brilliant vision of the apocalypse that hath ere been wrought! What a what a devastating portrait of society's collapse!”

All of us in the horror sphere were like, “It was good. But have you read The Stand? Have you read Swan Song?” It's bleak—I mean, it's Cormac McCarthy—but Blood Meridian is a billion times bleaker, I would say. But their sensitivity levels are so much lower. We have to be patient with them; they don't know. They're too used to Jonathan Franzen novels.

Going back to reading horror alongside classics—there’s a bit of discourse recently that has me shaking my fist at the clouds. There are so many women taking the TikTok to disparage Guillermo del Toro for concluding Frankenstein with a quote from Lord Byron. He was in a polycule with Mary Shelley!!

It's really sad, I think, to watch a two and a half hour movie and then discredit it because of what I thought was a very logical and thematically appropriate choice at the end.

I think I need to just log off and stop thinking about it. No one's making me engage in that discourse. But it's an interesting thing. I try to notice when I start getting too worked up about it, because that means it's time to put the phone down.

That's part of what I really want to evoke in my next book. My hope is that it can do for cell phones what Jaws did for sharks. Because I hate my phone, too.

It's always fascinating how, when you spend time away from social media, and then you hear about the latest controversy du jour that is happening, how small it seems when you're not in it. You're just like, “People are upset about that? I don't give a shit.” But when you're in it for a while, these things feel so important. So yeah, it is important to log off every now and then.

My love for horror is always renewed after these conversations. I've had a lot of very heartfelt conversations lately about the beauty of horror community.

The community is beautiful and wonderful. It's the best people. I'm working under the theory that the thing that makes a horror fan is a combination of two traits. One: immense anxiety. We are all very anxious as a community.

But there are plenty of anxious people that don't like horror. The thing that makes a horror fan a horror fan is that, whether we know it or not, we’re all inherently optimistic people. That's why we go to horror for that instructive value of like, how is survival possible?

I think there are people who are anxious and don't like horror because it's just confirmation that bad things happen. We don't get that same response. We watch a horror movie and we're like, how do I use this information and get to the end of this story?

That makes for a community that is full of really empathetic, warm, and supportive people. It's the best community to be a part of. I love all the horror people, and I love chatting with people like you, because these are bleak times, and we need all the connection that we can get.

And just like that—Nat summed up the exact thing I was seeking when I started writing this newsletter! To everyone reading: Thank you from the bottom of my haunted little heart. I love being in this strange little community with each and every one of you.

Up Next: Replay!

After publishing almost 90,000 words of Scare Me!, my first break starts next week. I have so much fun writing these newsletters that it’s hard to press pause—but I’ve learned the hard way that taking a break over the holidays is the best way to stave off burnout and prevent my brain from imploding.

I am pathetically addicted to beehiiv’s gamification, so I will maintain my publishing streak over the next two weeks by reissuing a couple of newsletters from earlier this year. They’re some of my favorite conversations from 2025, and I hope you enjoy them—whether you’re revisiting them or reading for the first time.

Finally: The holidays can be a weird and stressful time. If you’re working retail, feuding with your family, experiencing seasonal depression, getting triggered by ED demons, or just generally feeling anxious—I’ve been there, and I’m sending you all my positive energy. Hang in there!! I’m rooting for you!!

Scare Me! is a free weekly horror newsletter published every Thursday morning. It’s written by Michelle Delgado, featuring original illustrations by Sam Pugh. You can find the archive of past issues here. If you were sent this by a friend, subscribe to receive more spooky interviews, essays—and maybe even a ghost story or two.